Heroes have to remain heroes at all times. In

Sing All A Green Willow, Ronald Mason has written about having the legendary

AN Hornby, then in his seventies, pointed out to him on a Surrey road. The only action Mason could recall was "the manoeuvre by which he moved unobtrusively to the edge of the pavement and spat in the gutter". That was all. "With that sole independent gesture one of the greatest of all cricketing gentlemen passed in and out of my life."

Hornby is merely the starting point of a small list of Mason's heroes - Jack Hobbs, RES Wyatt, Walter Hammond, Errol Holmes. "A boy should have heroes," says Mason, "but when he is no longer a boy should they depart into the shadows with the rest of his boyhood?" Mason explains how he once got into a long explanation of his own batting with Hobbs ("It was worse than telling Shakespeare all about the one-act playlet I had just written for the tennis club social"), and consoles himself with the thought that all heroes worthy of the name let pass the solecisms of their admirers.

Mason, who has written excellent biographies of Hobbs and Hammond, muses thus: "It amuses me to think that if either had had second sight, he could have drawn the other aside on plenty of days at The Oval back in the lost twenties and said, 'Hey, Jack [or Wally], don't look now; but see the third boy on the left in Stand E eating sandwiches out of a cornflakes packet? Well, that's our biographer."

Sing All A Green Willow is not just about heroes. One of the essays is about

Frederick J Hyland, who earned an obituary in

Wisden as a first-class cricketer, although the only match in which he participated was limited by rain to two overs. Mason compares him to the "sparrow flying into the banquet hall, fluttering for a moment in the light and heat, and then flying forth at the far door into the wintry darkness". For after all, the man who has played first-class cricket is marked forever apart, by an indefinable aura of honour, distinction, achievement from his less fortunate though equally dedicated fellows who have not. And whatever the length of Hyland's career, he was a first-class cricketer, and how many of us can make that claim?

It is this mix of schoolboy awe and adult literary skill that informs Mason's writing. Like CLR James, Mason too wrote a study of Herman Melville (The Spirit Above the Dust) long before the novelist became fashionable. Mason was a civil servant who worked for four decades in the estate duty office in the "impressment and collection" of death duties. Perhaps he compensated for the morbidity of his professional calling with the grace and fluidity of his prose on a subject that was far closer to his heart.

Mason taught for a while, and it was some time before he turned his attention to cricket writing. His first effort, Batsman's Paradise, didn't enthuse the publishers till one of them sent it to Errol Holmes, the former Surrey captain, who said that he had no idea what was meant by the book's subtitle, An Anatomy of Cricketomania, but that he was sure the book was worth publishing. Mason was 43 then.

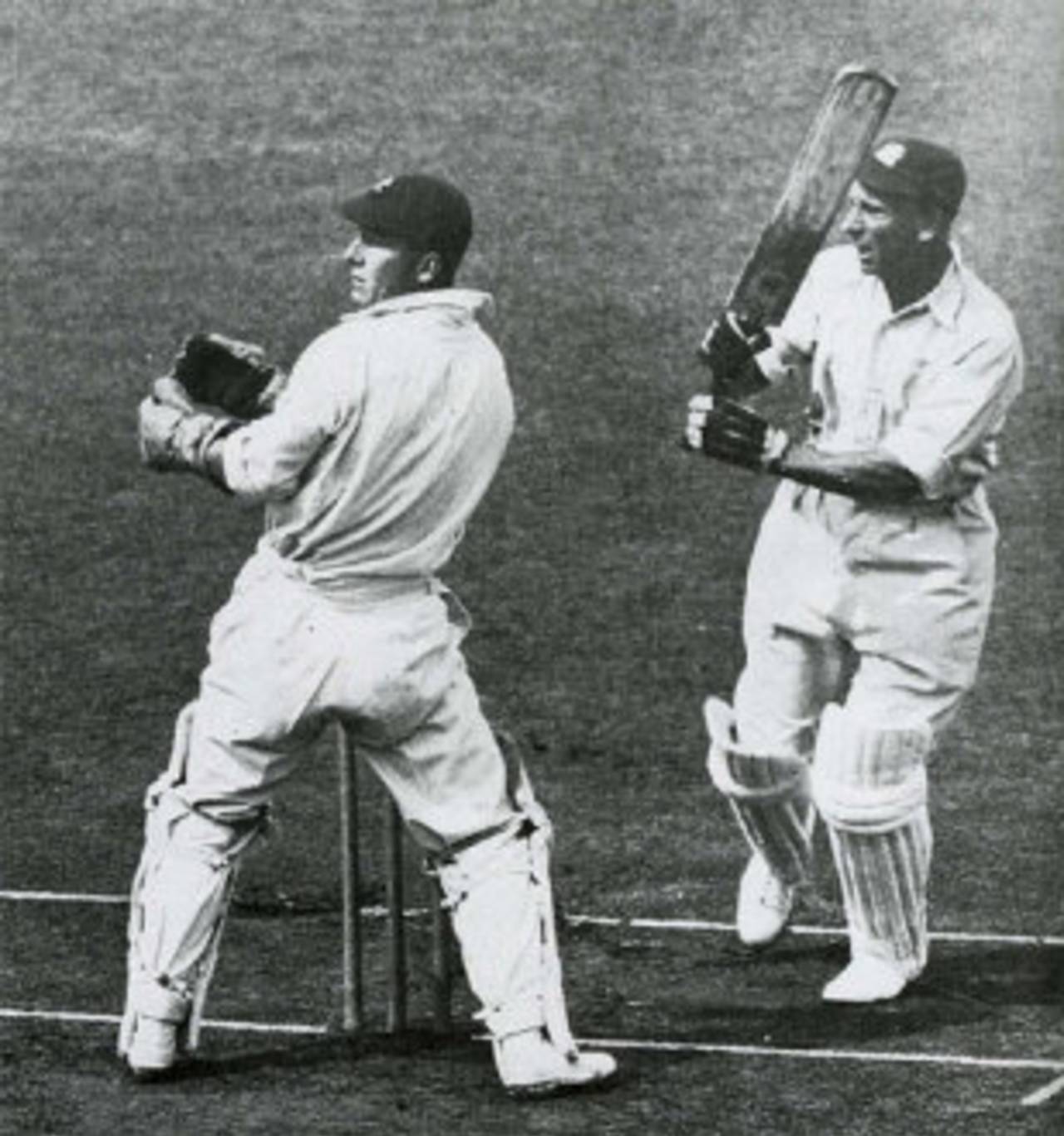

Five years later came the biography of Hammond. Mason wrote thus of his subject's bowling action: "Hammond's run-up like a bird's flight curve, and the splendid arching back of his body as he went into action, were only extensions, variations, comments on his great cover drive." With one deft stroke of his pen, Mason thus achieved a synthesis that the great player himself might have been unaware of.

In 1982, a half-century after the event, Mason wrote Ashes in the Mouth, the story of the Bodyline series. By then Douglas Jardine had been dead for over two decades, yet in an aside on Jardine and AW Carr, the two architects of Bodyline, Mason paid a tribute, "These two gifted players, who had each given great pleasure, disappeared with small thanks from the sight of a public that owed them more than they cared to remember." It said a lot about Mason himself.

Ronald Mason was 89 when he died. The Guardian wrote that "His great enthusiasm for the game was combined with scrupulous factual accuracy and a graceful, if at times flowery, style, over which he never lost control."

Suresh Menon is a writer based in Bangalore