Since their return to the international cricket family in the 1990s, South African sides have generally not been particularly popular with the wider Australian public. Captains such as Kepler Wessels set a tone in which they were often seen as negative and defensive. In the 2005-06 season

Graeme Smith managed to alienate a large proportion of the Australian cricket-viewing population, and at the same time lost five of the six Test matches. Smith tried to talk tough, but that approach dramatically backfired. It would not be unfair to describe Smith back then as one of the most unpopular cricketers in Australia since Richard Hadlee hung up his boots.

However, the 2008-09 season saw a dramatic turnaround in both public perceptions of Smith and the South African team. Smith's performance in that series as a leader was exemplary. He remained calm, and managed the media particularly well. He succeeded in transforming himself into a considered and mature captain who rarely appeared flustered.

When he walked out to bat, injured hand and all, in the second innings of the third Test

in Sydney during that 2008-09 series, Smith received a standing ovation from the entire crowd. It was reminiscent of the footage of the standing ovation for Harold Larwood at the same ground during the Bodyline series. While the public would have applauded Smith's bravery in 2006 if he had come out to bat in similar circumstances, he would not have won their hearts as he so clearly did in 2009.

Smith's recent retirement prompted thoughts about his cricketing legacy and my foremost memory was of him marching out to bat to try to save a match in spite of a serious injury. This resulted in consideration of other "brave" efforts from injured warriors who managed to return to the field to resume the fight.

One of the first examples that sprang to mind was that of

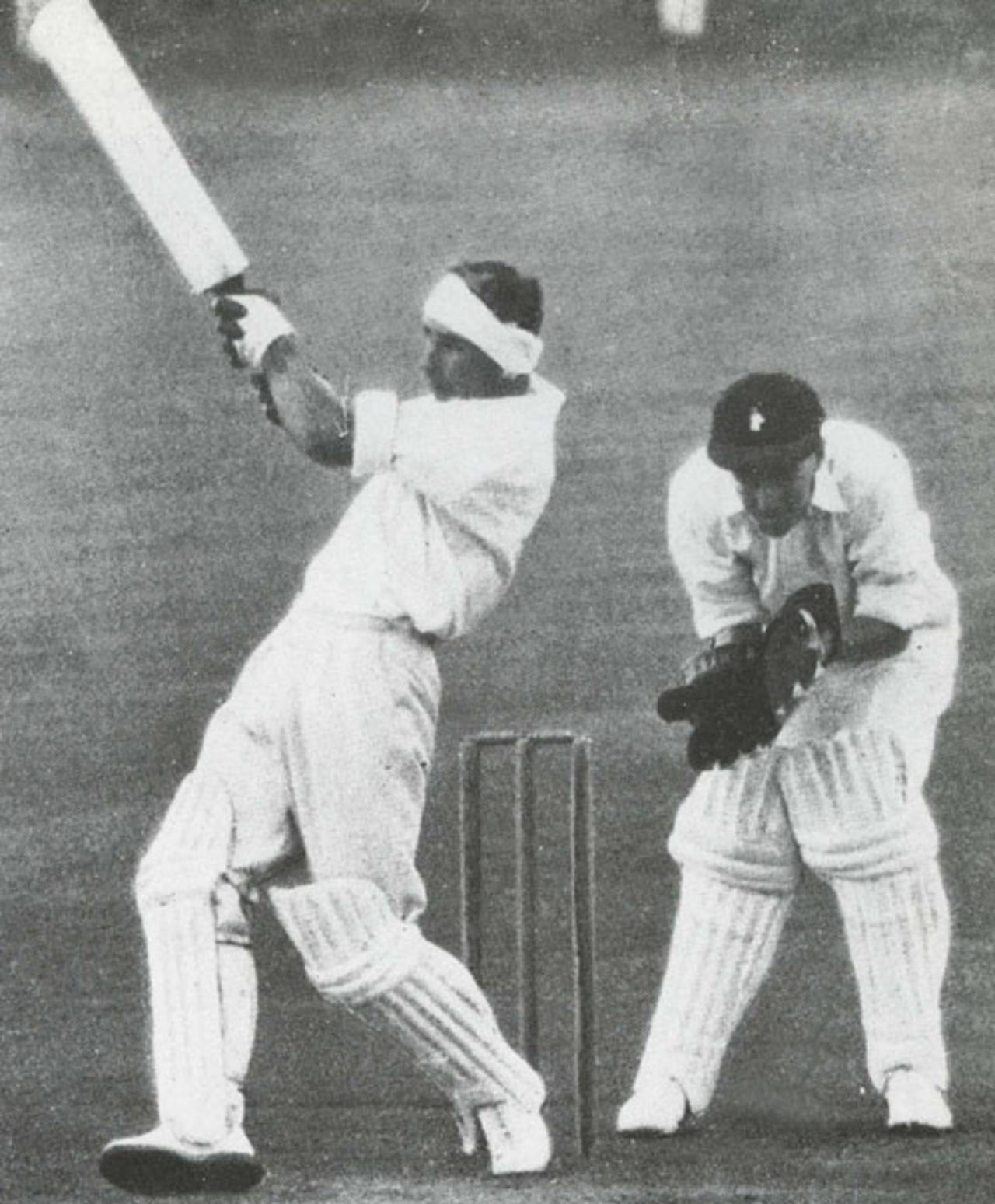

Lionel Tennyson, grandson of the English poet. He captained the English team during the 1921 Ashes series against the ultimately all-conquering Australian team. His opponent, Warwick Armstrong, had at his disposal the first truly great fast bowling duo, of Ted McDonald and Jack Gregory. The pair terrorised the English batsmen with sheer pace. However, in the

Leeds Test the Australian bowlers faced a fierce counter-attack by Tennyson. What made this innings remarkable was that he batted at No. 9 after the webbing in his right hand was ripped open while fielding and he had been thought unlikely to play any further part in the match. He scored 63 in rapid time and managed to scramble the home team past the follow-on mark, with Jack Hobbs unable to bat at all, and in the company of the No. 11, Cecil Parkin. Ultimately, England still lost the match but Tennyson's courage is remembered.

Another example by an injured English batsman came from the brilliant and unorthodox

Denis Compton. Much like Tennyson's, Compton's performance came against a very strong Australian team, led by Don Bradman and featuring a pair of fearsome quicks in Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller. At the

Old Trafford Test in 1948, Lindwall subjected Compton to a series of bouncers perhaps somewhat similar to the more recent Morne Morkel "assault" on Michael Clarke. Coming in to bat with the score a precarious 28 for 2 on the first morning of the match, Compton was struck on the arm and body before top-edging a hook shot into his head. In the pre-helmet days this type of injury was potentially fatal, and Compton was possibly lucky to escape with just a cut to his head that required him to retire hurt and get stitched up. Nonetheless, it was clearly a severe blow. Compton bravely returned to the pitch with England still in significant trouble at 119 for 5, and took his score from 4 to an unbeaten 145. The value of his performance is underlined by the fact that England's next best score in the innings was 37, but ultimately the weather won out with rain ruining any chance of a result.

One of bravest and most heart-rending performances in Test history occurred in South Africa

in 1953, when New Zealanders

Bert Sutcliffe and

Bob Blair shared a last-wicket stand of 33. In the larger scheme of things, a partnership of less than three dozen doesn't appear significant. However, Sutcliffe had been earlier struck a very nasty blow on the head by South African quick Neil Adcock, with New Zealand's score at 9 for 2. He was taken to hospital as a precaution, but then returned to the middle at 81 for 6 with his head bandaged up. He then smashed an unbeaten 80 including an astonishing seven sixes in less than two hours. What makes this situation even more poignant was that Blair batted with the tragedy of having just learned that his fiancée had been among the 151 people killed in the Tangiwai rail disaster on the North Island of New Zealand after a train bridge had been washed away.

I grew up in Inverell in northern New South Wales. Inverell has one major cricketing claim to fame: it was the stomping ground of

Rick McCosker before he moved to Sydney and eventually into Test cricket. It would therefore be almost sacrilegious of me not to mention McCosker's famous contribution in the

Centenary Test in Melbourne in 1976-77. A first-innings bouncer from English fast bowler Bob Willis broke his jaw. With Australia in trouble in the second innings, McCosker joined Rod Marsh with the score at 353 for 8, his head covered in bandages. McCosker scored 25 and ultimately the ninth-wicket partnership of 54 runs proved highly significant in that Australia eventually won by 45 runs. McCosker is now largely remembered for that one iconic performance, but many people forget that he actually played 25 Tests and averaged around 40 as an opening batsman in a period dominated by exceptional fast bowling.

One of my favourite performances by an injured warrior occurred during the 1981 series between Australia and the touring Indian team. Notwithstanding the obvious talents of Sunil Gavaskar and Gundappa Viswanath, the Australian public did not expect much resistance from the Indian batting line-up when facing the home team's fast bowling talents of Dennis Lillee, Rodney Hogg and Len Pascoe. The first Test seemed to reinforce this belief, with Australia winning by an innings. One of the few Indian batsmen who appeared to take the fight to Australia was the newcomer

Sandeep Patil. He had scored a good 65 in the first innings before being struck a fierce blow near his throat from Hogg. He shrugged that injury off, but was soon after hit again by Pascoe. This ball hit Patil over the ear, and he collapsed to the ground and was forced to retire hurt. These two blows must not have had an impact on his confidence, however, for in the next Test, just a few weeks later, Patil struck a

magnificent 174. Coming in to bat with India struggling in response to a massive Australian first innings, Patil was subjected to more short-pitched bowling but he batted beautifully and showed great mastery of all the bowlers. While Patil's return from injury was not technically within the same game, as it was with the other players I have mentioned, the mental scars must have still been fresh following the two serious blows in the previous match.

Of course, there are many other worthy examples including

Eddie Paynter leaving his sick bed with tonsillitis

to score 83 against Australia,

Colin Cowdrey batting with a broken arm against West Indies,

Bill Lawry returning to top-score after having ten stitches inserted into his forehead following a bouncer against South Africa, and

Malcolm Marshall, who batted with a broken hand against England. But of them all, I still consider Smith's performance as the most influential. It was a pivotal moment that we can identify as the point he moved from being generally disliked to being admired and respected as one of cricket's leading figures.